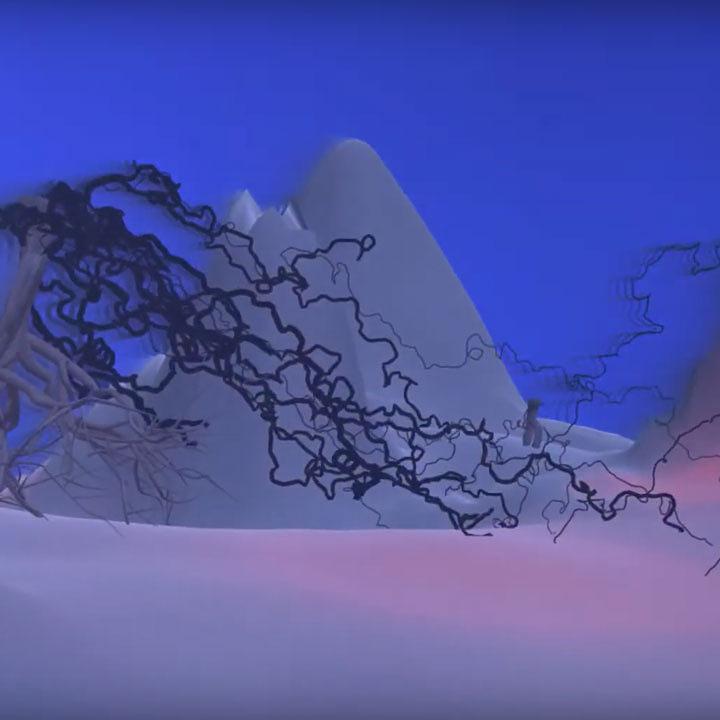

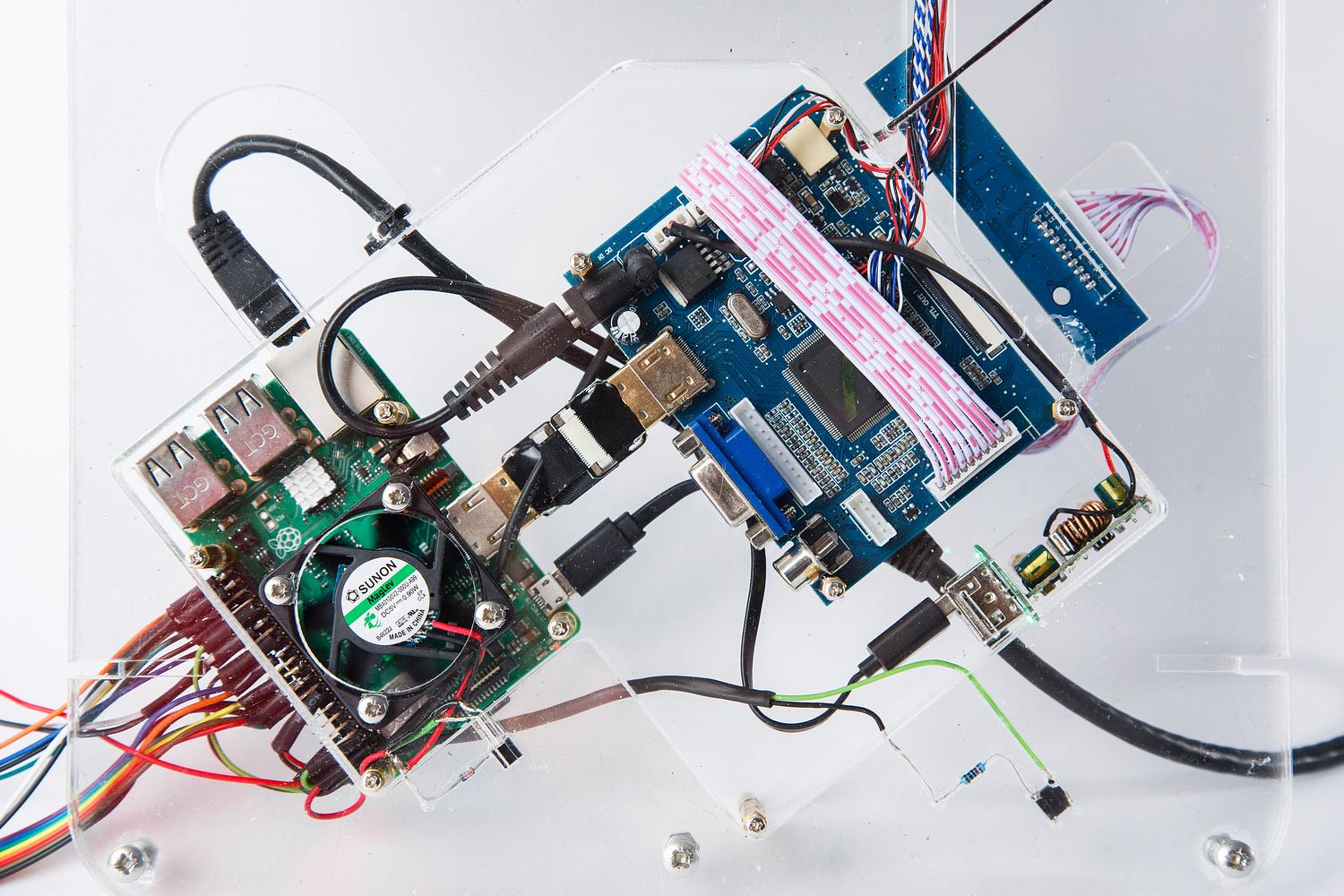

Performance Hydrogen City is the new site-specific performance by Digital Object Alliance invites visitors to experience the materiality of a speculative world of the future through the possible embodiment of videogame logics. The performance took place at Hyundai Motorstudio Moscow as part of the joint program by Garage Digital and the online platform Rhizome for the international exhibition World on a Wire.

1. Eron Rauch Virtual Light: Exploring In-Game Photography and Photo History

In-game photography, or something very similar to what we use this term for, has existed since at least the second half the 1990s. The characters in Donkey Kong caught the banana fairy with a camera; Pokemon Snap’s gameplay was based on photographing pokemons, The Sims suggested capturing a memorable moment for a family album; and the painter and multimedia artist Miltos Manetas was exhibiting his first screenshots and game videos in New York, London, Geneva, and Milan. But this trend become established in the early 2000s, with the triumph of social networks on the Internet, Steam turning into a platform not only for buying games but also for sharing screenshots, and the emergence of online hipster media publications writing about games in the same way as fashion or art.

The fact that in-game photography exists and is probably art was proclaimed by the German journalist Rainer Sigl in Videogametourism in 2012. Aiming to resolve the passionate dispute which erupted as a result, Los Angeles-based artist Eron Rauch responded to Sigl with a well-balanced text arguing that there cannot be a categorical opinion on the issue, while also explaining how much this echoes the protracted history of recognizing traditional photography as an art form (this medium, which emerged in the early nineteenth century, was not taken seriously by major art museums until the mid-twentieth century). Rauch identifies four categories of photography (not just in-game), based on the author’s intentions: vernacular, amateur, artisan, and art photography, which he defines as a conscious intention to enter into dialogue with the art of the past and/or the present.

2. Seth Giddings Drawing without Light

This 2013 text by Seth Giddings, Associate Professor at Winchester School of Art, raises more complex issues. Here, in-game photography is approached from the perspective of media theory. Giddings studies the intricate connections between in-game and traditional photography: clearly, this is about simulation, but what exactly is being simulated? Which ideas about the media basis of photography are reproduced in virtual reality? And what liberties are allowed for translation?

Returning to the moment of the invention of photography, the author demonstrates the difference between the technology of taking a picture and the concept of photography’s essence, which we eagerly (and recklessly) project into the past. An invention inevitably precedes the cultural tradition of its implementation, and it also changes while being conceptualized. An alternative history of photography appears before the reader, one that consists of mutations, sidesteps, and unrealized and marginalized alternatives (photography as a tactile process, X-rays).

Contrary to popular belief about the value of in-game photography due to its similarity to real photography, Giddings is primarily interested in such anomalies, as it is thanks to them that in-game photography becomes a genuine development of the photographic tradition, not merely a remediation.

3. Marco De Mutiis Photo Modes as a Post-photographic Apparatus

One such anomaly is analyzed in detail by Marco De Mutiis, a curator at Photomuseum Winterthur (Switzerland). Photo modes that became especially popular in the previous decade provide the player with an opportunity to put time on pause and later look for the best shooting angle. The usual course of the traditional photographic process, in which stopping time was always the result of shooting and not a condition of it, is reversed.

Studying this phenomenon’s socio-economic connotations, De Mutiis describes a rather obscure situation in which Vilém Flusser’s idea of a symbiosis between the photographer and the camera finds its continuation. In Flusser’s conception, the photographer does not just use an instrument but plays a game suggested by the camera. In the world of big data, seeing machines, and the economy of attention, the camera is more likely to dominate this pair, gently forcing the user to make actions, the content and ultimate goal of which remain concealed from them. Despite the promise of leisure inherent in the game and the promise of creative freedom which the photo mode holds, the player in this situation becomes a Kafkaesque character engaged in alienated labor. The majority of images from photo modes participate in economic relations, regardless of their authors’ intentions: this is a kind of free advertising, a propaganda tool within the graphic arms race.

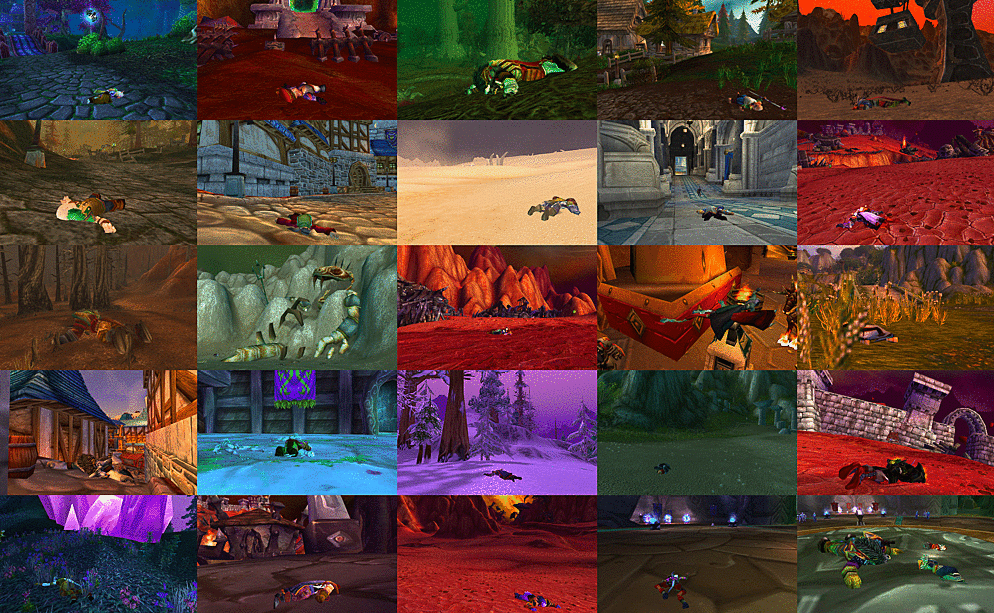

(A critical, Marxist interpretation of game visuals of this kind can easily be combined with the use of the described interfaces and with turning them against themselves: Eron Rauch acted in a similar way when he shot World of Warcraft in the mid-2000s from the viewpoint of the dwarf Guydebord, borrowing tactics from the Situationist arsenal).

4. Daniel Reynolds. Virtual-World Naturalism

Daniel Reynolds’ article examines the resistance to the prescribed rules of the game that an inventive and determined player can offer. The particular case considered here—“the naturalism of virtual worlds”—relates to the search for possibilities to overcome the virtual world’s geographical borders and explore behind-the-scenes spaces, through which one can sometimes unravel the history of these worlds and get a feel for the creators’ intention.

According to Reynolds, the naturalism of virtual worlds is a specific reaction to the fundamental changes in the methods of cognition that occurred at the beginning of the last century, when direct observation lost most of its former significance, giving way to laboratory research and data analysis. This is an opportunity to productively reproduce the cultural myth of geographical discovery, which is consonant with transgressive forms of interaction with urban space: the same paradigm of accessing forbidden territory which is traditionally associated with parkour and street art operates here.

Using the example of three games and the discoveries made therein, one of which cost the developers a few million dollars, Reynolds reveals the working mechanisms of this vernacular form of disobedience and explains the important role of the collective (and sometimes mass) character of these studies.

5. Jacob Gaboury. Screens Shot

Jacob Gaboury is a researcher into new media at the University of California, Berkeley. This series composed of five short texts provides a detailed analysis of the genealogy of the screenshot by tracing how and why people have taken pictures of computer screens over the past seventy years, and what role this practice performs today. The two most important structural changes to the screenshot are its transformation from an external operation into a programming one and the turn from capturing data to capturing how it looks.

Taking screenshots has evolved from a highly specialized and, in a sense, elitist practice into an integral part of the everyday (having previously managed to be a means of capturing tables with game records, which often show the results of bizarre processes, obviously not intended by the developers). The screenshot’s current popularity is the result of the total convergence of media, which has made the screen a universal agent in people’s relationship with any media form and a ubiquitous human companion.

For Gaboury, the screenshot is a visual imprint of a computational operation and a witness of interaction, capable of preserving the emotional and/or aesthetic content contributed by the user into the software environment. Despite their seeming insignificance, screenshots describe contemporary life more accurately than any other images and must be preserved if we want to convey its nuances to future generations.

6. The Early History of Machinima, 1996–1998 text in link is in Russian

The word “machinima” (from “machine” and “cinema”) refers to the practice of using video games to create moving images. Roughly, it means “in-game cinema,” which is not only recorded but also reproduced in the game, like a user’s cut scene. Having emerged around the same time as in-game photography, machinima gained recognition much more quickly (both in gaming and academic circles), but in the end it did not fit into YouTube’s ecosystem of game content and for the most part became a subject of interest to art galleries and marginalized enthusiasts. The text explores the very first works of this type, which largely appeared before the term defining them was coined: the rather monotonous experiments by Miltos Manetas in the form of gallery video art and user films by Quake players who were gradually moving away from describing game situations toward radical recontextualization and reflection.